This post addresses the question: How long does it take for a food-related trait to evolve?

We need a bit a Genetics 101 first, discussed below. For more details see, e.g., Hartl & Clark, 2007; and one of my favorites: Maynard Smith, 1998. Full references are provided at the end of this post.

New gene-induced traits, including traits that affect nutrition, appear in populations through a deceptively simple process. A new genetic mutation appears in the population, usually in one single individual, and one of two things happens: (a) the genetic mutation disappears from the population; or (b) the genetic mutation spreads in the population. Evolution is a term that is generally used to refer to a gene-induced trait spreading in a population.

Traits can evolve via two main processes. One is genetic drift, where neutral traits evolve by chance. This process dominates in very small populations (e.g., 50 individuals). The other is selection, where fitness-enhancing traits evolve by increasing the reproductive success of the individuals that possess them. Fitness, in this context, is measured as the number of surviving offspring (or grand-offspring) of an individual.

Yes, traits can evolve by chance, and often do so in small populations.

Say a group of 20 human ancestors became isolated for some reason; e.g., traveled to an island and got stranded there. Let us assume that the group had the common sense of including at least a few women in it; ideally more than men, because women are really the reproductive bottleneck of any population.

In a new generation one individual develops a sweet tooth, which is a neutral mutation because the island has no supermarket. Or, what would be more likely, one of the 20 individuals already had that mutation prior to reaching the island. (Genetic variability is usually high among any group of unrelated individuals, so divergent neutral mutations are usually present.)

By chance alone, that new trait may spread to the whole (larger now) population in 80 generations, or around 1,600 years; assuming a new generation emerging every 20 years. That whole population then grows even further, and gets somewhat mixed up with other groups in a larger population (they find a way out of the island). The descendants of the original island population all have a sweet tooth. That leads to increased diabetes among them, compared with other groups. They find out that the problem is genetic, and wonder how evolution could have made them like that.

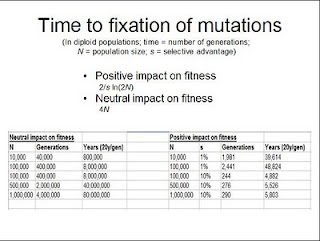

The panel below shows the formulas for the calculation of the amount of time it takes for a trait to evolve to fixation in a population. It is taken from a set of slides I used in a presentation (PowerPoint file here). To evolve to fixation means to spread to all individuals in the population. The results of some simulations are also shown. For example, a trait that provides a minute selective advantage of 1% in a population of 10,000 individuals will possibly evolve to fixation in 1,981 generations, or 39,614 years. Not the millions of years often mentioned in discussions about evolution.

I say “possibly” above because traits can also disappear from a population by chance, and often do so at the early stages of evolution, even if they increase the reproductive success of the individuals that possess them. For example, a new beneficial metabolic mutation appears, but its host fatally falls off a cliff by accident, contracts an unrelated disease and dies etc., before leaving any descendant.

How come the fossil record suggests that evolution usually takes millions of years? The reason is that it usually takes a long time for new fitness-enhancing traits to appear in a population. Most genetic mutations are either neutral or detrimental, in terms of reproductive success. It also takes time for the right circumstances to come into place for genetic drift to happen – e.g., massive extinctions, leaving a few surviving members. Once the right elements are in place, evolution can happen fast.

So, what is the implication for traits that affect nutrition? Or, more specifically, can a population that starts consuming a particular type of food evolve to become adapted to it in a short period of time?

The answer is yes. And that adaptation can take a very short amount of time to happen, relatively speaking.

Let us assume that all members of an isolated population start on a particular diet, which is not the optimal diet for them. The exception is one single lucky individual that has a special genetic mutation, and for whom the diet is either optimal or quasi-optimal. Let us also assume that the mutation leads the individual and his or her descendants to have, on average, twice as many surviving children as other unrelated individuals. That translates into a selective advantage (s) of 100%. Finally, let us conservatively assume that the population is relatively large, with 10,000 individuals.

In this case, the mutation will spread to the entire population in approximately 396 years.

Descendants of individuals in that population (e.g., descendants of the Yanomamö) may posses the trait, even after some fair mixing with descendants of other populations, because a trait that goes into fixation has a good chance of being associated with dominant alleles. (Alleles are the different variants of the same gene.)

This Excel spreadsheet (link to a .xls file) is for those who want to play a bit with numbers, using the formulas above, and perhaps speculate about what they could have inherited from their not so distant ancestors. Download the file, and open it with Excel or a compatible spreadsheet system. The formulas are already there; change only the cells highlighted in yellow.

References:

Hartl, D.L., & Clark, A.G. (2007). Principles of population genetics.

Maynard Smith, J. (1998). Evolutionary genetics.

No comments:

Post a Comment